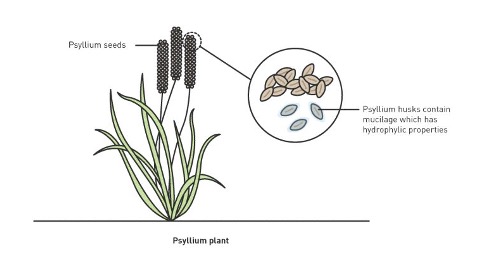

Psyllium, or ispaghula, is the seed husk from Plantago ovata [1]. Plantago ovata is a herbaceous plant, native to parts of Asia, North Africa and the Mediterranean. For centuries it has been used as a natural laxative; it is still popular in human and veterinary medicine to treat gastrointestinal disorders, uniting both conventional and alternative practitioners.

It contains multiple active compounds including methylglucuronic acid, various polysaccharides, oleic and palmitic acids, and arabinoxylans- which are thought to be responsible for the distinctive gel-like properties when psyllium is in contact with water [1]. It is readily available in powder or capsule form from pharmacies and health food shops.

Frequently psyllium is included in veterinary therapeutic diets or as a supplement primarily targeting gastrointestinal disorders. Research into the use of psyllium in human patients has noted satietogenic effects alongside a reduction of post-prandial hyperglycaemia in individuals with diabetes [2]. Gastroparesis also can be frequently observed in human diabetic patients and psyllium is used to promote gastric emptying- at the lower gastric pH, psyllium forms a more rigid, viscous gel, alleviating the symptoms of reflux, nausea and emesis [3].

A Focus on Fibre- how to compare from one diet to another?

All fibre is not created equal.

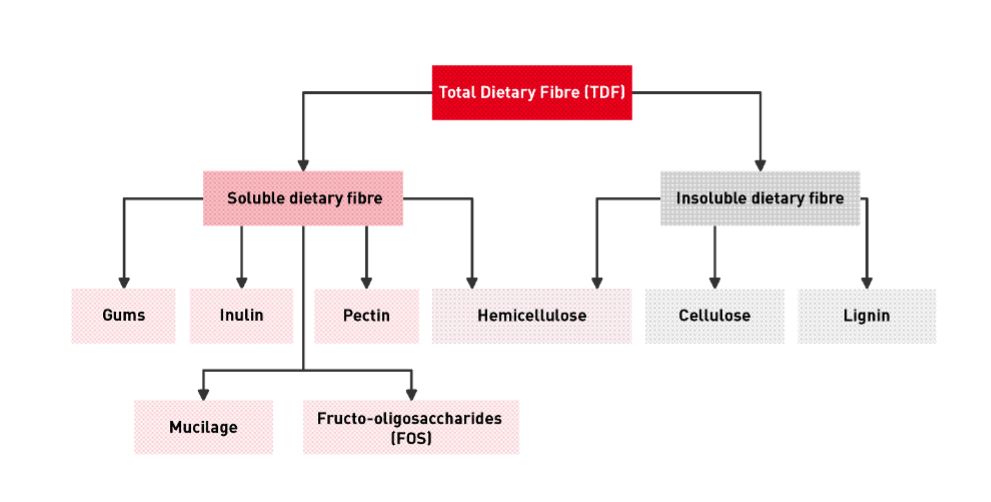

Fibre sources are analysed to determine both the solubility and fermentability and are usually categorized as such.

Soluble fibres – Using psyllium as an example, soluble fibres can form a gel-like consistency when in contact with water, which increases in viscosity in the presence of gastric acid and this can slow transit time in the stomach as well as increasing adherence of hairs caught by the pylorus [3, 4].

In addition to slowing transit time, the gel ‘traps’ nutrients and slows both the rate of transit and enzymatic breakdown, hypothesized to be the reason for the management of post-prandial hyperglycaemia and the satiety benefits observed in human studies in diabetic patients [2].

This ability to absorb water can also be beneficial in cases of diarrhoea by reducing the water content of the stool in the colon and increasing luminal volume [5].

Fermentable fibres – these are known to be actively digested by the predominantly bacterial population in the colon, releasing short chain fatty acids including butyrate, propionate and acetate which nourish colonocytes and support regeneration [5]. They contribute to maintaining a healthy and diverse microbiome. By providing energy to colonocytes, a healthy microbiome can benefit the absorptive and secretory capability of the colon [5, 6].

Insoluble fibres – Sourced from plant cell walls, cellulose and lignin are examples of insoluble fibre and do not ferment in the colon nor change structure in the presence of water; they provide a ‘bulk effect’. This increasing faecal volume promotes beneficial peristaltic responses and regulates gut motility. In cases of megacolon, increased insoluble fibre can maximise stretch receptor stimulation and maintain some movement. Insoluble fibres are extremely useful also in the management of hairballs, increasing faecal hair content and alleviating the gastric symptoms associated [4].

How determine the fibre content of a diet?

All diets on the European market are legally required to display the guaranteed analysis, which includes a value for Crude Fibre only (CF) [7]. This proximate analysis is based upon a system known as the Weende Method, which is over 100 years old [7]. CF values indicate only the amount of cellulose and hemi-cellulose. Lignification of fibre excludes measurement by this method; CF is not an accurate reflection of the insoluble portion and excludes soluble fibre sources.

Total Dietary Fibre (TDF) found on a guaranteed analysis label is a much more useful measure for comparison between two diets but is infrequently provided by manufacturers. The Van Soest and Englyst methods are much more precise to determine a TDF value but are not included in the statutory declaration on food composition in the US or Europe [7]. This creates challenges for clinicians when trying to make an informed recommendation to pet owners.

Uses in Royal Canin diets;

- Gastrointestinal range targeting;

- Colitis symptoms including diarrhoea associated with stress [5, 8]. Fibres have long been used to improve faecal consistency and regulate transit time. With the beneficial effects noted on colonocyte regeneration and surface area, recovery from diarrhoea can also be supported by fibre inclusion [5]. The production of fatty acids can also help lower intraluminal pH which creates an environment less favourable for pathogenic bacteria such as clostridium perfringens [8]Constipation. Psyllium has anti-spasmodic qualities, stimulating and regulating peristaltic action. There is also evidence of activation in muscarinic (parasympathetic) and 5-HT4 (serotonin) receptors known for their prokinetic action in the small intestine [1].

- Trichobezoars, more commonly known as hairballs [4, 9]. A recent study from the Royal Canin research facility in France assessed the addition of psyllium and increasing total dietary fibre TDF in a trial dietary ration on the faecal shedding of ingested hair [4]. The trial included both long and short-haired cats [4]. Prior to this study, most evaluation of hairball management was assessed simply via owner feedback, with no quantitative and objective measure. The trial showed significant increases in faecal hair excretion in the long-hair group when fed 11% TDF and 15% TDF formulations. The control diet had a TDF of 6%. As both the 11 and 15% TDF formulations included increases in both psyllium and cellulose, it is not possible to determine whether the soluble or insoluble fibre adjustment has the greatest effect on faecal shedding. There was also no significant difference between the 11 and 15% formulation results, suggesting using a diet with 11% TDF is sufficient to see a positive effect. Further studies will be required to determine the optimum combination of psyllium and cellulose.

- Diabetic range– When managing diabetic patients with nutrition, the goal is to provide adequate calories, correct/maintain body condition and minimize postprandial hyperglycaemia [6]. The focus is on carbohydrates in both simple and complex (fibre) form. Soluble fibres are used to slow gastric transit time, to trap macronutrients in the gel-like complex delaying enzymatic digestion and absorption, thus minimizing the glucose spike [2, 10]. Fermentable fibres also increase the production of short chain fatty acids (in the case of psyllium, predominantly butyrate), which consequently increases glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) production and release from intestinal cells [6]. GLP-1 plays a key role in the insulin regulation [6].

For owners who do not wish to adjust the diet but would like to add psyllium as a powder or capsule, a dosage range is recommended of 0.5-4.5 g/kg per day, titrated to response [8]. The psyllium should be given with food split into 2-3 doses per day and can be mixed with water to ensure adequate hydration.

- Mehmood, M.H., et al., Pharmacological Basis for the Medicinal Use of Psyllium Husk (Ispaghula) in Constipation and Diarrhea. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 2011. 56(5): p. 1460.

- Abutair, A.S., I.A. Naser, and A.T. Hamed, Soluble fibers from psyllium improve glycemic response and body weight among diabetes type 2 patients (randomized control trial). Nutrition Journal, 2016. 15(1).

- Harsha, S., H. Vincent, and Z. Jerry, Rheological Characteristics of Soluble Fibres during Chemically Simulated Digestion and their Suitability for Gastroparesis Patients. Nutrients, 2020. 12(2479): p. 2479-2479.

- Weber, M., et al., Influence of the dietary fibre levels on faecal hair excretion after 14 days in short and long-haired domestic cats. Veterinary Medicine & Science, 2015. 1(1): p. 30-37.

- Alves, J.C., et al., The use of soluble fibre for the management of chronic idiopathic large-bowel diarrhoea in police working dogs. BMC Veterinary Research, 2021. 17(1): p. 1-5.

- Greco, D.S., Chapter 37 – Diabetes Mellitus in Animals: Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs and Cats. Nutritional and Therapeutic Interventions for Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome, 2018: p. 507-517.

- McDonald, P., et al., Animal Nutrition. 8 ed. 2022: Pearson Education, Limited.

- Leib, M.S., Treatment of chronic idiopathic large-bowel diarrhea in dogs with a highly digestible diet and soluble fiber: a retrospective review of 37 cases. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 2000. 14(1): p. 27-32.

- Donadelli, R.A. and C.G. Aldrich, The effects of diets varying in fibre sources on nutrient utilization, stool quality and hairball management in cats. Journal of animal physiology and animal nutrition, 2020. 104(2): p. 715-724.

- Xiaohong, X., et al., Effects of enhanced viscosity on canine gastric and intestinal motility. Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2005. 20(3): p. 387-394.

Written on November 30, 2023.